An appetite for cheap inventory and tolerance of low-quality ads has sowed the seeds of mistrust among advertisers. Ben Bold reports.

Like any advertising medium, digital attracts its fair share of both optimists and pessimists. The former group tends to enthuse about the seemingly inexorable growth of digital advertising, as it meets and even exceeds the levels of spend enjoyed by traditional media, while offering advertisers value for money.

The latter bemoans the crude, slow-loading or just plain annoying ads that intrude consumers’ desktop or mobile screens, or points to the growing frequency of ad fraud that means brands are paying for ads that never reach their audiences.

Then there are, of course, the realists, who sit somewhere between the two, passionate about the medium, but equally sceptical about its shortcomings.

Adam Smith, futures director at GroupM, who recently authored the WPP agency’s ‘Interaction 2016’ report, is quick to point out that the acceleration of digital advertising is anything but symptomatic of an industry facing crisis, while remaining under no illusions about the threats overhead and looming on the horizon.

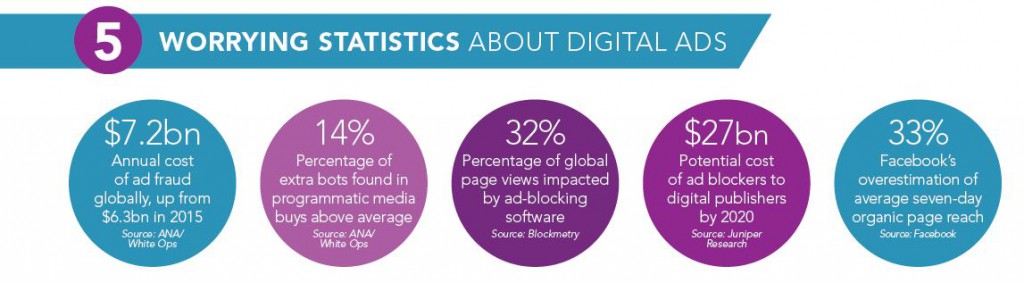

Yet storm clouds are undoubtedly amassing. The prevalence of digital ad fraud is backed by some alarming estimates, with one figure estimating it at $7.2bn in 2016, putting it on course to become the world’s second-biggest criminal enterprise after the drugs trade.

“That should be enormously concerning from a moral perspective as well as its potential impact on brands,” says Tim Gentry, who spent nearly 20 years at Guardian News & Media, latterly as global revenue director, and who is now a consultant working with a range of media businesses.

He points out that the figure, as astronomical it is, is merely “the tip of the iceberg”. “We’re not scratching the surface of all the long-tail sites that exist,” he says. “Fraud manifests itself in a number of ways – some legitimate businesses buying fake eyeballs, with some illegitimate sites pretending to be one publisher, when they’re nothing like it.”

WILFUL OBSTRUCTION

While ad fraud means that ads are not reaching the eyeballs of their target audiences, despite advertisers paying for the privilege, other ads are escaping the fraudsters only to be obstructed wilfully by consumers who have downloaded ad-blocking software.

“The technology and gaming communities are the ones that adopted native ad blockers first. It’s as high as 40% for gaming and tech sites,” says Steve Chester, director of data and industry programmes at the Internet Advertising Bureau (IAB). “Broadly, lifestyle sites see much lower incidences, sometimes as low as single digits, of ad-blocking.”

The IAB’s own research into ad-blocking, based on a YouGov sample of 2,000 adults, found in July that 21.2% of adults are currently using ad-blocking software, compared with 21.7% in February, a marginal rise. However, around 20% of those who said ‘yes’ were confusing ad blockers with anti-virus software and other non-ad-blocking software, meaning an adjusted figure of around 16%.

“I think if you’re a publisher or media owner, it should be of concern,” Chester adds. “I certainly think there is a lot that people can do to take control of their destiny. If you’re a brand or agency, it amounts to a loss of audience, which is not good.”

“If a newspaper or TV channel shows ads in the wrong place then the advertiser gets their money back. There’s no recourse in digital”

How is it then that in a discipline that employs the sharpest minds on the planet, the rise of fraud and ad-blocking have been allowed to happen?

“What makes it possible is greed,” says Smith. “One of the odd things about the internet [and digital advertising] is that if you’re an advertiser and you’re only prepared to bid 10 cents for a click, you will always find someone to sell to you. It’s down to a fixation on price and a refusal to question anything too good to be true.”

Gentry concurs. “Businesses are focused too much on short-term results,” he says. “It’s not their fault, it’s what the industry sold as the benefit of the medium. But we’re going through that shake-up now where everyone is realising that it’s no longer sustainable.

“If you talk to agency CEOs involved heavily in the pitch process with marketers, quite often the conversation is around the issue of quality and transparency. There is a trade-off for these things, in that, as with all aspects of quality, it comes at a price.”

Smith cites another reason why ad inventory is failing to deliver. “The risks haven’t been properly costed,” he says. “If a newspaper or TV channel shows ads in the wrong place then the advertiser gets their money back. There’s no recourse in digital.”

Ad-blocking take-up, on the other hand, is being fuelled by something more prosaic, and less criminal.

“The biggest reason for [people using ad-blocking] is advertising that interrupts their experience,” says Chester. “It might be an ad that gets in the way, that flashes, or audio that suddenly blares out.”

He adds: “What we’ve seen as we gravitate towards mobile-first is that as publishers try to monetise mobile because CPA rates on mobile cost less than desktop, the yield has gone down, which is encouraging some to go for more intrusive advertising, like overlays.”

FIGHTING BACK

But both fraud and ad-blocking can be combated. Google’s DoubleClick is one such defence, while a study by the Association of National Advertisers in the US that unearthed an agency culture involving non-transparent practices such as rebates has brought the issue to light.

“We will never be complacent,” says Smith. “I do think that fraud can be defeated by careful planning. In other words, be careful of the company you keep, and screen suppliers.”

Chester agrees. “The caveat is that it varies considerably, but we’re seeing more instances and greater sophistication of fraud,” he says. “More people are taking measures to prevent fraud, such as better detection – if you have a more direct line of sight to where you’re buying and from whom. We’re encouraging all members to use fraud-detection software.”

Meanwhile, industry-wide movements are being formed to battle ad fraud. The IAB is part of JICWEBS (the Joint Industry Committee for Web Standards in the UK and Ireland), which represents media owners, buyers and advertisers from industry bodies the IPA, ISBA and the Association of Online Publishers.

“We all got together under the umbrella body looking at trading standards,” Chester says. “We’re building an accreditation system under which anyone that trades has to be certified in terms of how they are reducing the risk of fraud.

JICWEBS is also working with TAG (Trustworthy Accountability Group) in the US to conduct a number of initiatives to try to eradicate fraud by introducing a blacklist and ID system.

Likewise, the insidious rise of ad-blocking too can be stemmed with a focus on better-quality ads, observers claim. “From all the conversations we’ve had, I can’t think of one in which anyone said that we want advertising to be intrusive and annoying,” says Chester, half joking. “What we’re seeing the debate about is where the line is.

“An ad can’t be so discreet that it disappears, but it can’t be intrusive. The challenge is to achieve an equilibrium.”

It is this objective that has led to industry-wide initiatives such as ‘The Coalition for Better Ads’, a global project backed by the IAB and advertisers including Procter & Gamble and Unilever and the likes of Google and Facebook. In essence, its proposed solution is straightforward – make less intrusive ads that don’t piss off consumers.

The advertising industry is also talking to lawmakers and police across the globe about measures to help detect and prosecute ad fraudsters. But does this notion of official intervention apply to the regulatory frameworks that govern advertising; or should it?

Gentry questions how practical and implementable such rules would be. “I think that regulation in the digital industry is so difficult in terms of its pace of change,” he says. “You need to be fast enough to regulate the industry.”

MEASUREMENT AND AUTOMATION

In a discipline so enriched by, and simultaneously complicated by, the huge volume and granularity of data available, it is little wonder that there are calls for better measurement technology to help advertisers quantify and qualify exactly where their money is going.

“When you’re advertising, try to build in mechanics or devices that are hard for fraudsters to fake,” explains Smith. “We have a walled garden of our own, a data spine, in the US, UK, Netherlands and Germany, where we have anonymised profiles of users, so when you’re dealing with inventory from the web you can run it through our filters.”

Automation is also part of that answer, he argues. “Programmatic started as a market-clearing remnant tool for cheap media. Now it has become the opposite, a means to pull data into the buying mechanism. I think that’s an important safeguard, avoiding criminals by ingesting more data.”

Half of digital buying is now automated, up from around 40% last year. Smith proposes that it ideally should rise to 90% of bought media, with the remaining 10% managed manually to make “sure that the robots are working”.

“Advertisers are voting with their wallets and moving spend away from non-transparent sources of media to sourced media”

The IAB’s Chester welcomes the growth of programmatic. “With programmatic on the rise, we’re likely to start seeing a shortening of the supply chain,” he says. “If the industry really wants to minimalise ad fraud then it needs direct deals, buying from named sources like The Guardian, knowing where the inventory is going.

“It’s not to say that programmatic on open exchanges is bad, just that the risk is higher. There’s a shift towards private marketplaces.”

At the heart of the issue is the need for the advertisers to push for greater transparency across the supply chain.

“I remember hearing Mondelez talk about combating fraud and they seemed to have a very sensible solution,” reveals Gentry, “saying to suppliers and partners that ‘unless you can tell us exactly where our money is going, we’re not investing in you’.

“It’s incredibly simple, while the reality of executing on that is incredibly complicated. Advertisers are voting with their wallets and moving spend away from non-transparent sources of media to sourced media.”

If clients and agencies lead, then others will follow. “Ultimately the pressure needs to come from the clients and agencies. The latter are very active in this space,” adds Gentry.

“While they have been such beneficiaries, because they are big organisations, perhaps Google and Facebook are not the answers that brands need. Google represents the whole web, and that’s good and bad.”

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The latter point is especially resonant given Facebook’s recent admission that a raft of errors had led to it overestimating its metrics (and effectively overcharging clients).

“Facebook put out its confession about the mistakes it’s making around measurement,” says Smith. “It was making schoolboy errors, and the idea of them marking their own homework is a worry.”

To be fair, Facebook has made moves to prevent a repeat, recruiting Unilever and Nestlé to its new ‘Measurement Council’. But the debacle highlights a particular concern among advertisers. “Clients worry about the sellers making the rules,” says Smith. “Making them convenient to the seller or that the seller might suddenly change the rules.”

There is clearly a long way left to go before ad fraud is anywhere near to being stamped out, or at least brought to heel; while ad-blocking will remain an issue so long as there are artless, slow-loading or intrusive ads. So what can we expect to see? Will things get worse before they get better?

“If the appetite for cheap inventory grows and a tolerance of low quality rises, then the problems rise with that,” says Smith. “But they’re not going to rise from the agency-bought business.”