In the latest chapter of ‘The Media Men’, a compilation of stories of the founders of today’s agencies, Festival of Media Global speaker Nick Manning reveals how lessons in history can help guide and drive the next generation of advertising leaders.

History lessons from a life in advertising

In the age of programmatic media and Artificial Intelligence, what can we advertising Old Guard possibly teach today’s ‘digerati’?

Well, as Sir Winston Churchill said, “those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it”, so this is my attempt to help today’s Bright Young Things learn from my successes (and mistakes) to help their own career paths.

In today’s exciting digital age it’s easy to lose sight of some of the essentials that remain true about the advertising industry. It has become more complex, fragmented and technical, to the extent that the wood sometimes get lost for the trees.

This piece addresses the need for today’s rising industry stars to rediscover some of the essential motivating factors that drive the advertising industry and make it stronger.

Having mentioned one Conservative Prime Minister already, I will echo another, John Major, in urging a ‘back to basics’ approach to the future of our industry.

The first part of the article documents my own odyssey, with some lessons that hopefully apply today, while the second part takes a look at how the industry should recapture some of its traditional objectives and values.

Part One: lessons from the past

First things first; this is about advertising, not media. I have always considered myself an ‘adman’ first and foremost, and I just happened to ply my trade in media planning, buying and latterly analytics.

Advertising sometimes gets bad PR, ironically, but at its best it makes a significant contribution to the economy through demand creation. Advertising helps build brands, products and services by connecting content with audiences, so even if you’re currently beavering away in, say, pay-per-click search optimisation, you’re in Advertising, too.

Building a career in advertising is still a great way to be in business, but don’t forget that it is a business, first and foremost, and that it’s better to have a career than a succession of jobs.

All’s well that ends well

My own career didn’t get off to the best of starts.

I’d been in my first job in advertising for three months, and it was first review time. My direct-talking boss delivered his verdict on my performance thus far, summed up with the word ‘adequate’. I was damned with faint praise, but was kept on. Adequate was just about good enough.

I nearly didn’t go into advertising at all. I was a graduate in Modern Languages, so the Careers Office at Oxford came up with an unimaginative list of career choices such as Insurance Broking and Advertising. I failed to get into advertising via the well-worn route of the ‘milk round’, traipsing around advertising agencies, competing with other fresh-faced graduates for one of the coveted graduate positions as an trainee account director.

Failure was inevitable as I knew very little about advertising (or business), hadn’t researched it much, and probably didn’t really know or care too much about it. I was conditioned to know I needed a job, but not how to get one. In those days, everyone coming out of school or college got a job of sorts quite easily, and internships were unknown. However, getting into the ad agencies was hard even then, and the rejection letters duly arrived.

And I nearly didn’t go into the media side of advertising at all. The smart folk at the Careers Office told me that only highly numerate people should consider media planning and buying, so a Languages graduate wouldn’t go far.

So after advertising rejected me (and I had incorrectly rejected Media), my default option was insurance. It didn’t suit me and I didn’t suit it.

Then good fortune struck. A school friend of mine was selling TV advertising airtime to agencies. He’d been approached for an interview at a media agency for a role buying TV airtime, but he didn’t want to leave his current job. Fortunately, he suggested I go for the interview instead.

It all sounds implausible now, but I was a substitute interviewee brought off the bench without any real knowledge of the industry.

So I sat across the desk from Barry Croucher, the man who later used the ‘adequate‘ word, and when he asked me what my academic qualifications were, he started laughing. It turned out that my description of my exam track-record as ‘the usual‘ (9 ‘O’ Levels, 3 ‘A’ levels at the top grade and a degree from Oxford) was not so ‘usual‘ in the world of media. Barry was the proud owner of one ‘O’ Level and joined the industry straight from school, as many did in those days.

I’d gone from the ad agency ‘milk round’ where everyone had top-flight degrees after glittering Public School careers (First XV, Head Boy, etc) to a more obscure part of the industry which most people had joined without troubling the higher groves of academe. When I joined Chris Ingram Associates (CIA) in early 1980, I found myself to be one of the very few graduates in one of the very few (at that time) independent media agencies.

CIA had been set up in 1976 by Chris Ingram, one of the leading lights of the Media Independent movement. He also became the most successful of the new generation of pioneers, eventually selling his company for a lot of money, allowing him to become a serious patron of modern art and the owner of Woking Football Club (not normally associated with each other but there is probably a ‘statues’ joke available).

Having started as a trainee TV planner/buyer, I went on to be one of the team who helped pioneer the independent media agency sector (now a multi-billion dollar business) and I subsequently co-founded a media agency which continued the legacy of the early Davy Crocketts such as Chris.

I got into the industry through luck, but these days anyone applying to enter the industry would be expected to be both interested in (and ostensibly passionate about) working in Advertising, would have done lots of homework, would almost certainly have had relevant internships, and may have a number of interviews, including test exercises. It’s much more competitive now, and people have to work hard to get in through the front door (or know someone who can let them in at the side gate).

Internships do matter. One sure-fire way of triage for an interviewer when looking at a big sheaf of CVs is to favour those candidates who have earned some early stripes in a related role, even if unpaid, and especially if the word ‘digital’ is on your CV, contrived or not.

And while internships can get you up the leader board, a strong CV is vital, with extra-curricular achievements as well as good academic qualifications. So think ‘personal statement’. A lively interest in business is mandatory.

OK, it’s a cliché, but advertising is still one of the best, most exciting industries to be in, especially if you don’t want the predictability and slightly stultifying (for me) rigour of the ‘real’ professions (don’t write in). For those who thrive on variety and a slight sense of trepidation, there isn’t much that can beat it. But you have to work hard to get into it, and really want to. If this applies to you, you’ll get in. And if you work hard enough, you’ll do well.

So you’ll like advertising if you like variety. If you prefer something more predictable, stop at accountancy in the careers alphabet.

I started ‘adequately’ in this industry but worked hard and developed a strong interest in the business. It can lead you to many interesting places populated by many fascinating people.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose

The advertising world has changed beyond recognition, largely thanks to technological change and globalisation. The media industry has been transformed, with thousands of ways of reaching and engaging with people through an almost infinite array of channels and content options.

However, there was also plenty that was new when I joined the industry. Channel Four only began broadcasting in November 1982, two years after I started, and in the 80s and 90s we were having fun inventing new ways to use TV and other existing media.

Yet the fundamental role of marketing and advertising hasn’t changed. Business still needs to find innovative ways to attract new customers, build demand and generate preference. Half the fun is inventing better ways to gain the public’s attention. The job’s the same, even if we’ve swapped ITV for Instagram, and magazines for mobiles.

However, the media agency world really has changed. CIA was one of the first standalone ‘Media Independents’, a new concept for advertisers who did not need or want flashy ads, but needed good media planning and buying (well, mostly low cost buying). These clients were among the early adopters of the new Media Independents who aimed to kick sand in the eyes of the flabby, complacent advertising agencies. This wasn’t ‘proper’ advertising, filmed in Barbados, but it was K-Tel Records and the Ronco ‘Buttoneer’ (look it up). Low cost production and low cost media did the job.

In those days, the traditional Ad Agencies did everything for the ‘proper’ brands, and they enjoyed a seat at the right hand of the client Top Brass; the fees were generous, the fine wine flowed freely and weekends shooting on country estates ensued.

However, a group of maverick, entrepreneurial media directors from the Ad Agency sector saw an opportunity to carve a niche for themselves by setting up independent businesses which only did media planning and buying. Those pioneers were the progenitors of the massive media buying groups of today, although none could have foreseen just how far the independent media agency sector has travelled since the mid-70s.

The journey was fraught in the early years. The Ad Agencies didn’t like the upstarts trying to eat their expensive lunches, especially as media was the most lucrative aspect of the Ad Agency business; they received 15% commissions on the money spent by their clients and it was easy income, with no real conditions attached. The Ad Agency sector of the 1980s enjoyed a boom time, with plenty of nice offices, cars, parties and much powdering of noses.

Like the wine, money flowed freely, but little reached the basement level where the troglodyte, less expensively educated media folk lived, so some of the media directors saw an opportunity to elevate media into a proper business.

At that time media was infamously allocated ten minutes between the end of the creative presentation and lunch. The long-suffering media directors had to engage clients in the rather less interesting world of spots and spaces, while stomachs growled around the room and the ‘suit’ held up five fingers instead of the expected ten.

I have been fortunate to both witness and participate in the development of the media agency business from those embryonic days in the 80s to today’s world, where the media agency networks are global, employ many thousands of people, provide a glittering array of services to clients and generate hundreds of millions of pounds in profit for their shareholders.

However, the 70s Wild West was a rough old place for the settlers who set up their own media agencies. The concept of independent media services was controversial and unpopular. The Advertising Agency sector did its best to snuff out the embryonic media independents as they represented a real threat to the most profitable part of their business. Some of the breakaway ‘meeja johnnies’ were looked down on, having joined the industry straight out of school, and that school wasn’t Eton.

For us novice foot soldiers it was a steep learning curve. I began my career as a trainee TV buyer, securing ad slots on the UK’s TV stations, ranging from the bigger London players (Thames and London Weekend Television) to the small but perfectly-formed Border TV, at just 1.2% of the UK population and 5% of the sheep.

Quaintly, TV airtime was bought via a series of ‘options’, a choice of ad slots in programmes which were read out over the phone and recorded by us in illuminated script by quills on parchment (well, not quite). In those days, the target audiences were as sophisticated as ‘All Adults’, rather than the highly sophisticated segmentation-derived programmatic pseudo-audiences of today. And people really were a lot more alike in those days anyway.

We entered the bookings onto our outsourced booking system (TEMPO) by filling in electrostatic punch-cards. These were collected in the late afternoon, sent off for processing overnight and our map-sized print-outs would arrive the following morning, minus the spots where we’d filled in the punch-cards incorrectly (well, it was often done after a liquid lunch). There were no desk-top computers in those days, and tablets were things that Moses took for headaches. People met or spoke to each other on the phone, which seems hard to believe these days.

Oh, and most of our TV spots were ‘pre-empted’ (outbid) on a (rigged) auction basis, long before Google, so huge amounts of our time were wasted; but we had so much time available that no-one complained too much. Maybe real-time bidding isn’t so original after all.

Thirty seven years on, it’s interesting to note how much has changed, but also how little. The industry has a history of reinventing itself, but the principles remain the same. Innovation is a constant, and in the 1980s we invented new ways to use media. Today the opportunity to innovate is infinite, and that’s a large part of the attraction of the business for people who like to stretch their imaginations.

So, whatever your role, stretch the boundaries and try something new. See each day as a learning opportunity.

Those were the days…weren’t they?

I began in a three man department and we enjoyed ourselves. Much of the business with the TV sales houses was done person-to-person, usually at lunchtime and always with plenty of alcoholic assistance. For some people afternoons didn’t really exist and they woke up late at night in the railway sidings.

On Fridays we would decamp to a leafy suburb, have a real lunch (with food in it) and graze through the afternoon without a thought about work, as there was little work to do.

These were politically incorrect times, and one of our team (OK, the boss) kept a selection of ‘exotic’ magazines in a filing cabinet for the amusement of some, but it wasn’t unusual back then for daily banter to mimic the very worst of the ‘Carry On‘ movies, which turned sexual innuendo into a sort of art form. My Jesuit schooling hadn’t prepared me for this, but it was like a second childhood with added multiple entendres.

‘O Tempora, o mores’, as I thought but didn’t say at the time.

The Media Independent sector grew in strength and simply provided advertisers with better media planning and buying. We cared about our craft, and were able to out-perform the Ad Agencies by being more expert, agile, and cheaper.

I flourished once I’d finally got the hang of it and found myself rising rapidly through the ranks of a small business, being made a board director within five years. This doesn’t happen much these days, but the pace was different then and people could get promotions and pay rises at a rate that doesn’t exist in the megalithic media agency world of today, unless you’ve got ‘digital’ in your job title.

I’ve worked hard (sometimes) and played hard at other times, but we did a good job for our clients. As a result, CIA grew and grew, as did the other Media Independents, and the sector was getting too powerful for the somewhat complacent Ad Agencies to ignore. In time, they would be obliged to join in the party; one turning point was when Saatchi & Saatchi, the poster child of the Ad Agency world, acquired Ray Morgan & Partners (a successful Media Independent) to form Zenith, now a large, global media agency network in the Publicis group.

It was perhaps inevitable that the new Media Independents would look at merging to accelerate growth, or for some founders it was a chance to cash in their chips. CIA and TMD, staunch rivals, seriously considered getting together, a possibility which led us senior CIA people to consider a breakaway. We plotters met in a bar called the Tappit Hen just off Trafalgar Square, and over copious quantities of red wine hatched our plan to set up on our own if CIA merged with TMD. Fortunately none of this happened, saving us from ourselves; we were serious but incredibly naïve, but everyone was learning back then.

CIA floated on the junior stock market in 1988 and the founding shareholders were able to crystallise the value of their early years, but those of us who hadn’t been there at the start missed out. The flotation did allow CIA to buy a lesser rival called Billett and Co the following year, and we found ourselves with a new boss, the eponymous founder of the acquired company.

Four of the key directors, including myself, had a sense of having helped build the business but had missed out on the flotation. Knowing when to move on is another constant in a career path, and those of us who had missed out on CIA’s flotation began to prepare our exits.

Fortune favours the brave…again

Serendipity intervened, as it often does. It was quite common in those days for the Media Independents to provide media services to a new generation of creative ad agencies, who were busily eating into the business of the older and somewhat flat-footed agencies, by the simple means of producing better creative work.

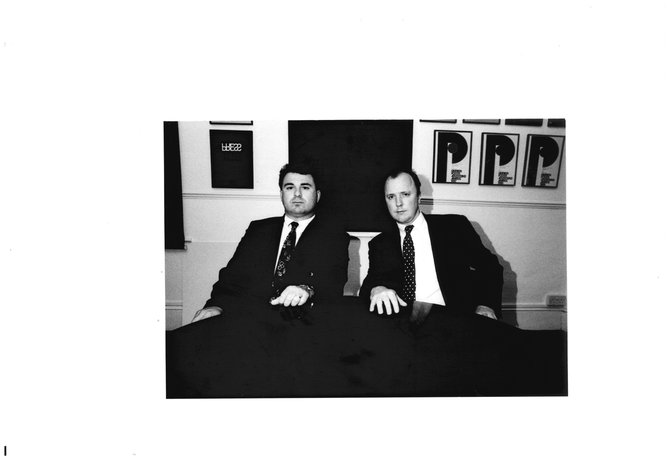

One such agency was the snappily-named Simons, Palmer, Denton, Clemmow and Johnson, a highly entrepreneurial start-up with big ambitions. They came to see CIA, and I talked to them alongside a colleague called Colin Gottlieb. We hit it off with the Simons Palmer team, and soon afterwards we became their outsourced media planning and buying partners, forming a successful combination. So successful, in fact, that Simons Palmer approached Colin and myself to break away from CIA and launch a media agency business with them instead.

We called it Manning Gottlieb Media, MGM for short.

We wanted to create a business where media would make a significant difference to our clients. We wrote a ‘manifesto’ for the business, including the following words written 27 years ago, and relevant now:

We wanted to create a business where media would make a significant difference to our clients. We wrote a ‘manifesto’ for the business, including the following words written 27 years ago, and relevant now:

“Given an ever-increasing choice, today’s media literate generation is developing a butterfly mentality in their media use…viewers, listeners..are swiftly moving targets and, as media specialists, we have to adopt an equally light-footed approach to media choice and tactics.

MGM has been created to put imagination back into media.

MGM will deliver what advertisers really need-imaginative media solutions allied to sharp negotiation. In other words, media that sells.”

Colin and I resigned directly to Chris Ingram in August 1990. We were joined by another CIA stalwart, Robert Ffitch, and I can vividly recall the three of us shuffling nervously into Chris’s office, armed with our resignation letters. This was all rather unexpected from Chris’s point-of-view and he asked for time to think about his response. When we informed him that there would be an article in the following day’s edition of Campaign, the advertising trade publication, it was obvious to Chris that we were on our way.

Setting up our own business just felt right. I’m a big believer in instinct, and we didn’t look back as we set out on our new adventure. Creating one’s own business remains many people’s ambition, and we were diving into it headlong. That’s often the best way.

If you’re the kind of person who fancies taking a risk or two and setting something up, there is still little to beat it.

From humble beginnings….

Manning Gottlieb Media began its official life that August, but Colin and I were obliged to spend our three months’ notice period on ‘garden leave’, so away from the office but on-call, while CIA attempted to shore up the client relationships that we had painstakingly nurtured.

Colin and I were not free to join our own agency until November 1990, when we took up residence in Simons Palmer’s offices. Robert Ffitch effectively began MGM before we arrived, and remained a stalwart of the agency until 2016, helping it to achieve great heights over 26 years.

We were joined shortly afterwards by Hilary Taylor (now Jeffrey) and we formed the agency based on a successful formula which continues to this day, 27 years on. One reason for our success was teamwork and the relationship between Colin, Robert, Hilary and myself. We had specific skills and worked very effectively together.

We heard that one CIA Director had charmingly predicted that we’d be ‘dead in the water by Christmas’, but a number of our ex-clients came with us, for which we remain suitably grateful.

However, we had launched into a recession. We initially sheltered in the sponsoring warmth of Simons Palmer’s swish and expensive offices in Noel Street in Soho; these were tough times for us all, but we placed our first ad, a small, black and white space for Greenpeace, and we were underway.

Meanwhile, we had received a phone call from David Reich, the boss of TMD Carat, our toughest competitor. David bought a 19% stake in our business for £66,000, and TMD Carat provided us with ‘air cover’ and added credibility. David’s investment would eventually pay back handsomely.

New business was not slow to arrive, with Simons Palmer succeeding in persuading some of the clients they won to include MGM in the service. Some of the earlier wins were small, such as the Science Museum, but later on a number of significant spenders such as Nike and Virgin Atlantic came in from this route.

As a brand, Nike was only just setting out in the UK in the early 90s, and Simons Palmer and MGM were appointed to handle the non-TV business. This led to some innovative uses of outdoor media (thanks to Colin) which broke new ground at that time, and helped burnish our reputation.

One day my brick-like mobile phone rang and a former CIA client requested a meeting; he’d moved on to another company called Helene Curtis, and they wanted to launch a new brand called Salon Selectives. Could we help?

We began work shortly after without a ‘Request for Proposal’, or a pitch and initially without a contract, and thus began a highly rewarding client/agency relationship, and a major boost to our business.

In 1995 we and Simons Palmer jointly won the launch of Sony’s new games console, the original PlayStation, leading to another long-term relationship, and the Goldfish credit card followed in 1996.

Clients like Nike, Virgin and Goldfish were ‘disruptor’ brands who needed something innovative, both in creative and media terms, and we delivered in spades. Some of the advertising produced by Simons Palmer still stands out as examples of how great work can help transform the fortunes of a brand, and it certainly inspired us.

The Goldfish credit card launch in 1996 was remarkable primarily because it involved a number of agencies working intensively together over a three month period, and it remains a textbook example of integrated thinking, planning and execution across a range of channels represented by different specialist agencies. It’s what clients today say they miss.

The best advertising work comes from experts from different disciplines working together to create something special; this is still true today. And the experts don’t all have to work at the same company, but need to share a common purpose.

Whatever your role, you should aim to work in harmony alongside people who represent other aspects of the industry. It provides a better result and is more interesting and enjoyable. But don’t be precious.

The best of times…the worst of times

MGM prospered because we forged extremely close client relationships and produced great work. The advertisers we suited best wanted creativity in media; we provided this and got to know our clients very well. They trusted us, we worked incredibly hard and produced innovative work. We put our clients first and this is still the best way to grow a business.

Proof of this came when Simons Palmer lost the Virgin Atlantic account when Richard Branson (ennobled later) hated their first TV commercial and they were fired. MGM however had done great work and held onto the media business when the creative account was awarded to another new agency, Rainey, Kelly, Campbell, Roalfe (another example of snappy agency names). Our relationship with RKCR also turned into a strong, enduring one, and we produced some of our best work while partnering with them. The three-way relationship between Virgin Atlantic, RKCR and MGM was the best of any I’ve known. We respected each other and the client folk trusted us all.

Around this time, Zenith was launched as the first real ‘factory ship’ for bulk media buying, and the trend towards the commoditisation of media began. Our relationship with Carat helped, as they enjoyed strong credibility in the media buying market; we were able to claim that our clients enjoyed the creativity of media planning and good media rates, and this was not only true, but arguably what some clients say they lack today.

In a bland, undifferentiated market, MGM stood out for our constructive approach to media owner relationships, which seemed perfectly logical to us but wasn’t the norm. The media owners found us receptive and accommodating, unlike so many of our rivals, and helped us innovate in media. Relationships with media owners are even more valuable now.

MGM had fled the Simons Palmer nest in Soho and set up in their original space in Covent Garden, a small warren of offices that suited our slightly offbeat approach. Independent businesses that succeed usually attract potential purchasers. MGM was no exception, and we had a few clumsy overtures and even looked seriously at being acquired by PHD (who set up a year before us) to form the ‘Harlem Globetrotters’ (without the height) of the new media agency world, but perhaps fortunately that didn’t happen.

Simons Palmer, our sponsor and shareholder, was acquired in 1997 by TBWA, an advertising agency within the Omnicom group. As a result, we found ourselves part-owned and within the orbit of one of the big marketing communications groups.

This was a welcome development as it opened up international horizons for MGM. As a UK business, our ability to grow was limited and especially so in an industry which was rapidly globalising. This began in earnest when the media departments of two of the oldest Ad Agencies, JWT and Ogilvy and Mather, were fused into MindShare, arguably marking the point where the unbundling of media from Ad Agencies came of age.

Shortly after TBWA bought a minority stake in MGM, Colin and I set out for New York to see Omnicom, TBWA’s parent company. Fortunately Colin did most of the talking, as usual, as we sat (nervously in my case) with the Chairman and CEO of Omnicom. The conversation went well and so we became majority-owned by TBWA, and therefore Omnicom. We’d joined the big league without wholly giving up our autonomy by virtue of retaining a shareholding; Carat exited handsomely, after an interesting eleventh hour attempt to buy MGM themselves.

Retaining a stake worked very well for us. We still felt like it was our business, and we could make sensible business decisions rather than pump up the profit.

Following the Omnicom deal, MGM became Manning Gottlieb OMD to signal our new ownership. Our agency enjoyed a purple patch during the dotcom boom with a crazy rash of new business. It was like the Klondyke Gold Rush; we were interviewing daily and offering jobs on the spot, knowing that any candidates would be snapped up by someone else if we didn’t get there first. Tim Pearson, the current CEO of Manning Gottlieb OMD, was one person we hired on the same day as his first interview.

We doubled our headcount in a year. This level of growth was unhealthy, and when the dotcom crash inevitably happened, Manning Gottlieb OMD suffered accordingly.

Just before the crash, Omnicom had decided that it needed to strengthen OMD’s operations and turn it into a fully-functioning international media agency network. This would prove to be a hugely complex and difficult job, so they wisely chose Colin Gottlieb to do this in Europe. They needed someone of his drive and determination to carry out a tough plan, so Colin effectively left Manning Gottlieb OMD to become the CEO of OMD’s operations in Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA), a role he continues brilliantly to this day, and now as CEO of Omnicom Media Group in EMEA.

I found myself as the sole CEO of the agency Colin and I had founded, at a difficult time for the world. The nadir was a meeting on September 12th 2001, the day after the 9/11 attacks. The world felt like it was collapsing that day. We had some of the senior Omnicom people in London for a tough conversation and they couldn’t even phone home to their families. It doesn’t get any worse than that. The events of 9/11 put everything into a different context, and made our own difficulties seem insignificant.

We had seen the best and worst of times in short order. Triumph and disaster are impostors, as Kipling said, but ups and downs are a natural cycle in life and in business. It is easy to forget this during the less good times. It’s worth remembering that all things do pass, and it’s only business. Time heals.

Into the modern era….

The next turning-point was one of the most important in this narrative, both for me and as part of the wider industry trend towards globalisation.

Colin’s appointment as CEO of OMD EMEA was a concerted attempt by Omnicom to form a proper media agency network to compete with the others.

Colin swiftly turned OMD’s European operations into a powerful player. One breakthrough moment was when OMD won the European business for Sony in 2002, a point at which we also began to emerge from the economic headwinds of the dotcom crash.

Manning Gottlieb OMD had worked with Sony Music since 1997, and this was the first time that we had worked alongside OMD UK, who had the Sony Consumer Electronics business. The partnership worked, albeit with the growing pains of two teams collaborating for virtually the first time.

The most significant aspect for me was that I became an international media person overnight, with no prior experience. I was charged with running both the Sony Music and Sony Pictures accounts across Europe, and I set about doing this as though it was the most natural thing in the world.

Around this time Manning Gottlieb OMD hit some choppy water, and in hindsight I had failed to take the right steps to backfill my CEO’s role, especially with one bemusing attempt to have three people jointly run our agency. I had yet to fully learn the classic tenet of ‘one ship, one captain’, and a strong clearly-defined leader of any business is critical.

So is focus, and I’d become distracted by the new attractions of international business. Running a media agency is more than a full-time job.

Pride comes before a fall….

In 2002 we had won the AA (previously Automobile Association) business, with the best pitch presentation we’d ever given. We came up with media ideas which stand the test of time, firmly rooted in the creative idea. It was another breakthrough, proving we could handle a large client and make very significant media cost commitments as part of OMD.

Times were good. Memories of the dotcom crash were receding, and there was a real sense of pride and achievement, and as we headed off in August 2003 to our Summer party, the sun shone, we played games (‘It’s a Knockout’) and the team was on great form.

So maybe I didn’t think too much about a call I got on my way down to the Summer party venue from a client asking to see me more or less immediately.

The client informed me that he had offered to set up two of our key people in their own business by offering them his account, which was pretty significant at that time.

The two people in question (Andrew Stephens and Ben Hayes) were two of our star performers, so we stood to lose two great operators and a big chunk of business. So, without thinking too hard about it, nor even asking permission, I told Andrew and Ben how hard it is to operate in a tough, competitive market such as the media agency world, so why didn’t they allow Manning Gottlieb OMD to take a stake in their business to provide the kind of ‘air cover’ we’d enjoyed from Carat in 1990? It had been a good lesson.

Andrew and Ben said ‘yes’, and their business, Goodstuff, has gone on to great things, including being voted ‘Media Agency of the Year’ by Campaign magazine.

Playing in the Big League…

The following year, 2004, was even more significant, both for me and the development of the media agency industry.

I was asked by Colin Gottlieb to lead OMD’s operations in the UK. The media agency market had evolved still further, with more consolidation and internationalisation. The big communications groups were actively forming quasi-holding companies and Omnicom was no exception.

Subsequently Tess Alps, then in charge of PHD, and I set out to create a joint venture to bring together the negotiation power of OMD and PHD. We created OPera, a company which would act on behalf of OMD and PHD in a number of common areas, including media negotiations.

The Summer of 2004 was the hardest period of my entire career. My new role involved pulling together a number of business entities across three different buildings with very disparate cultures. It was tough, but it worked.

I aimed to make the process of harmonising the OMD UK Group as consensual as possible, as I am firmly of the view that people like to be involved in determining their futures. It takes longer but it’s worth it.

Through perseverance, teamwork and goodwill our team succeeded in reshaping the business to meet the new media environment, and I decided that it was time to move on to the next challenge.

Knowing when to pass the baton on to the next generation is never easy, but there is a right time for everything and this was it. I had been in the media agency world for 27 years, and I left it in April 2007 with great memories of the people I’d met along the way, many of whom remain friends to this day.

The next chapter…to the present day

I knew I needed a change, but I didn’t know what it would be. I was excited rather than daunted by the absence of anything on the horizon. One common characteristic of this story is maybe that some inner self-confidence tells me that opportunity is always out there.

In October 2006, I had been reintroduced to Michael Greenlees, who had started and grown an advertising group called Gold, Greenlees, Trott in the 1980s. It was successful, floated, grew rapidly and was eventually also acquired by Omnicom, around the time MGM was acquired. I only met Mike once, briefly, in 1998 before he moved to the USA and was made CEO of TBWA Worldwide.

After his time in New York, which had also included periods with other companies, including a private equity player, Mike and his family were moving back to the UK. A mutual contact suggested we talk together and so we met in a hotel on Wimbledon Common in October 2006, close to where we both lived. We found that we shared a lot of views and values, and kept in touch as various opportunities emerged.

I had enjoyed numerous other conversations with interested parties, and was on the verge of joining another agency group when Mike persuaded me to join him at a company called Thomson Intermedia (TI), which I barely knew. The company had floated on the AIM index of the London Stock Exchange in 2000 but had not grown in line with expectations. The founders, Steve and Sarah-Jane Thomson, had agreed to stand aside and hand over to a new management team. Mike had been offered the role of CEO, and asked me if I’d like to join him.

TI had acquired in 2004 a company called Billetts, founded by the person whose media agency CIA had acquired in 1989, not long before I left CIA. John Billett had gone on to create a successful company which specialised in media benchmarking, a service whereby advertisers could compare their media performance versus pooled averages. TI was in the business of advertising monitoring, providing competitive information, and wanted to access the Billetts data to provide a picture of how much advertisers were really spending using average media pricing.

Michael and I walked into the TI offices on Charing Cross Road on September 27th 2007. I knew very little about the business and had to start from scratch.

By this time we were in the throes of the global economic downturn caused by the implosion of the financial markets in 2007/8. We were getting used to new expressions such as ‘sub-prime’ and ‘credit crunch’, while getting to grips with a relatively complex business. It was a tough time for everyone, and we started the process of rebuilding the business in the face of strong headwinds.

We rebranded TI corporately as Ebiquity in September 2008, and transitioned our client-facing businesses to the Ebiquity brand on February 14th 2011. We had moved to new offices which were brighter and better, and we set about growing the business.

We embarked on a series of acquisitions which both broadened our geographic coverage and also our range of services. I travelled around the world as we acquired companies in such diverse places as Russia and Australia.

In 2012 we acquired another international media benchmarking business called Fairbrother Lenz Eley; this was an interestingly circular move as it had been established by Ian Fairbrother, who had been my closest colleague in the TV buying department at CIA when I joined the company in 1980. Ian had gone on to create his own successful business in media measurement.

During this time, I learned a huge amount about business generally under Michael Greenlees’ tutelage, and was heavily involved in the expansion into other countries and our acquisitions. My career previously had been very UK-based, but my time at Ebiquity has led me to travel all over the world, seeing places and meeting people that have opened my eyes in various ways. They say that travel broadens the mind, and it has much the same effect on the waistline. However, I cannot recommend getting involved in international business highly enough.

We have been turning Ebiquity into a broadly-based marketing analytics business, operating globally with particular strengths in media measurement.

We summarise Ebiquity’s purpose as ‘creating clarity’ in a world that offers immense choice to advertisers, where data is critical and with new skills needed to make sense of the plethora of data available. There is no question that the advertising industry is now much more interested in measurement and accountability, and proving its value to the advertiser. Whether all the right things are being measured is debatable, but the trend towards measurability is strong and laudable.

While Ebiquity is very different to the media agencies, it mirrors the changes in the industry that have affected the agency business. Globalisation and the role of data analytics are two of the key features of the modern media world, and anyone setting out to build a career in advertising should aim to be a global citizen and get to know as much as possible about the technology and data driving today’s industry. You don’t need to be a statistician or data geek to thrive in this new world, but a smattering of the new language is helpful (especially as acronyms are rife).

It’s also a good idea to understand the new marketing industry, where customer and user experience are important parts of the way companies build their business.

I spent 27 years in the media agency world and now ten years at Ebiquity. It’s a long time, but the advertising world changes constantly and I learn something new every day. It’s never less than interesting and the shape of the industry continues to provide limitless opportunity as well as the kind of problems it is interesting to solve.

Ebiquity lives at the heart of industry change, helping advertisers get to grips with the dynamic nature of the market. We also help them get the basics right, as they still count too, as John Major pointed out.

Part Two: Back to basics

My 27 year career on the media agency side provided highly rewarding experiences based around relationships, teamwork and doing things better. We worked hand-in-glove with our clients and their other agency partners, mostly in harmony, and we sweated blood to make their advertising work harder.

We knew our clients’ business inside-out, went to their sales conferences, sat through their (often very dull) research presentations, and bought their products. We prided ourselves on our expertise, and strove to provide fresh and orginal ideas, coupled with high standards of media strategy, planning and execution. We cared, deeply and perhaps naively.

A strong bond of trust grew between ourselves and our clients, and we put their interests first.

It worked and the money followed. We earned every penny and delivered great value for our clients, often neglecting our own best interests in the pursuit of client success. This still seems like a natural way to run a service business.

The globalisation of the advertising industry has changed the industry for ever. The big holding companies provide a dazzling array of resources to advertisers, and have responded to the need to broaden their services while delivering globally.

There is an increasingly important role for media agencies to play in a world of infinite choice for advertisers. It takes huge expertise and experience to help navigate advertisers through the turbulent waters of the new media ocean, with data analytics increasingly driving decision-making. There is no doubt that the media agencies have a bright future, especially as they broaden their proposition.

However, this comes at a price and the economic model for media agencies has been stretched by the client need for more services more quickly, and their ability (and sometimes willingness) to fund them. The media agency market is still wildly competitive, despite consolidation, and some media agencies have expanded their revenue sources through media trading-related means to fund the expansion of their services and increase or maintain profitability.

It can be argued that the media agencies (or, more accurately, their owners) have become embroiled in a tug-of-war between their duties to their clients and their obligations to their shareholders. It’s a difficult circle to square.

A case in point was the 2016 study in the US market, conducted by the ANA, where media trading incentives were examined. Results from a sample-based study showed that some media agencies may be receiving benefits from media owners in return for spend commitments.

In a world where such incentives exist, the bond of trust between the client and their media agencies may become looser, as clients may ask questions regarding their media agency partners’ commercial interests.

Trust will only be restored when clients agree to pay appropriately for the services they receive and media agencies adopt transparent models of trading. This will take some years to happen, but it will be essential if the advertising industry is to attain the level of professional robustness we should all aspire to.

As part of its 2016 initiative, the ANA commissioned Ebiquity to provide recommendations for its members as to how they should achieve better accountability and transparency in media. I spent several fascinating weeks in the US with some of the smartest people in the industry trying to find a better way of working. Whether we succeeded will be judged by others, but in many ways we set out to recreate the conditions in which MGM used to thrive: a real dedication to client success, where the financial rewards were shared in the right proportions.

One of the most attractive characteristics of the advertising industry has always been its contribution to the economy. Advertising boosts demand for goods and services and supports the premium branded market. Advertising provides content that informs and entertains (at its best). Advertising may suffer from bad PR at times but it has traditionally been both popular with the public and seen as beneficial.

However, the growth of digital and the new emphasis on data may have led to a loss of some of this perspective. Increasingly, advertising is being used for short-term gain, rather than long-term brand-building.

Some of this may be down to general short-term thinking within companies (who may be under pressure from shareholders), but it can be argued that the apparent instant gratification of online advertising may have contributed to this trend.

It is possible to measure the response to online advertising and paid-for social media via clicks and ‘likes’, but these are flimsy ways to determine success. Some brands who work on a direct-sell model may benefit from online advertising driving people to their websites, but many brands do not have the luxury of such a close link between advertising and sales.

At MGM we worked with great creative agencies such as TBWA, Simons Palmer and RKCR, and the combination of original, well-crafted creative work and considered media thinking led to both short-term and long-term business results.

Companies such as John Lewis have shown that really powerful creative work can be effective both short- and long-term, but the headlong rush for lower-cost efficiency has arguably led to a dilution of creative standards and potential harm to brand health.

Some of the craft of advertising has been lost to automation. The lathe has given way to the laser, but the best products are often produced by workshops, not factories.

This applies to media just as much as it does to creative content. Good media planning comes from a strong understanding of the client’s business, their customers and how those customers interact with a range of channels (not just the ones you can advertise on). The right research and data has always been critical, but now the job cannot be done properly without it, and planning should be conducted neutrally. Channel selection that is pre-determined by bias or media trading considerations may lead to compromises that can harm effectiveness.

While much has changed in the 37 years since I joined the ad industry, the basics remain reassuringly unchanged. Good advertising is still the result of great and clever creative work (so, content) that touches a nerve with its audience and attracts their fleeting attention.

But that work has to reach the right people in the right way, and that’s still crucial, too. There is a lot of art to good media, and while data is now vital to the creation of good media, the combination of right and left brain cannot be beaten, even by the savviest of tomorrow’s robots.

Change is constant in media, and change should be welcomed. Much of the career satisfaction to be derived from working in the advertising industry comes from never being sure what will happen next. This is what makes it endlessly fascinating.