In the latest chapter of ‘The Media Men’, a compilation of stories of the founders of today’s agencies, Festival of Media Global 2016 speaker Stephen Allan recounts how he chose the path of media and never looked back.

Growing up, I loved photography – that was my passion. So, frankly, at the age of 16 or 17, I thought there was no point in going to university. I couldn’t see the benefit. I started looking at advertising photography, checking out the spreads in the colour supplements – trying to work out, “how did they do that?”

By about the age of 17 and a half I realised that I possibly wasn’t good enough in my own right – or related to the Royal family – to make the kind of living I wanted as a photographer. But the advertising industry – that looked interesting, so I decided that I should look at that a bit more closely.

I started looking for information in libraries, career rooms – anywhere I could find – , and I read about the job of an ‘account director’. And I thought, okay, I’ll be an account director.

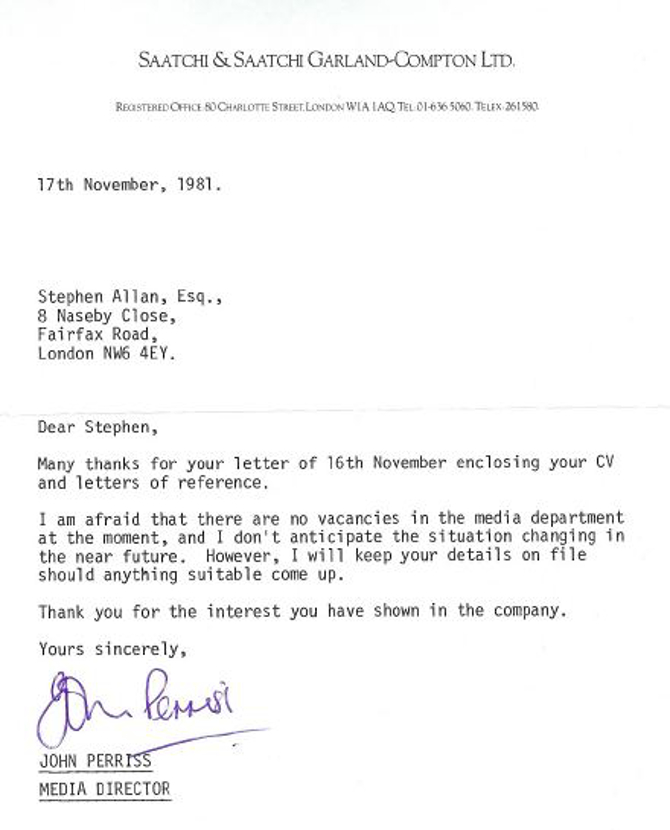

It turned out it wasn’t quite that simple. I wrote to 80 agencies, and I got back 80 refusals.

I didn’t know anyone in advertising. My father didn’t know anyone in advertising. I wasn’t sure what to do, so I just started talking to anyone who would listen to me about what I wanted to do.

One day I was – quite literally – talking to someone at a bus stop, and she said, “My next door neighbour’s called Michael Peters. He’s something to do with advertising, I could introduce you.”

It turned out that he was really a top guy in the design and packaging field. He agreed to see me, and he proceeded to tell me all about this “line”. Did I want to be “above the line” or “below the line”? I was thinking “what’s this line?”. In the end I said “above the line”, because that sounded better. And Michael said he would put in two calls for me, one to Charles Saatchi – whose name really didn’t mean anything to me at the time – and one to Mike Yershon.

He made the calls in front of me. The Saatchi call went nowhere, but this Yershon guy said, “Send him along”.

As I was thanking him, Michael Peters said to me, “Just don’t get his name wrong. It’s Yershon.”

So I went round to their offices above Caesar Shoes in Bond Street, and I walked in and said, “Good afternoon, Mr Gershwin.” It wasn’t a good start.

AN INTRODUCTION TO ‘MEDIA’

He couldn’t offer me a job, but he did offer me some holiday work experience. I went back a few weeks later, by which time they’d moved offices to the Swiss Centre. (I’d been a hundred times for tea with my German grandparents to the Swiss Centre, and never noticed there was an office block above it.)

My first job on day one was to analyse TV ratings – the blue and the green books, as they were then – for football programmes. Mike’s company was doing some consultancy work for The FA.

I spent two weeks sitting on the floor, working on this project, and I really enjoyed it.

It wasn’t advertising. It was definitely not Mad Men. But I enjoyed it.

At the end of the two weeks, he said he wasn’t able to offer me a job, but he was pleased with the work I’d done and would give me a good reference.

I took his reference and wrote to some of the agencies I’d written to before, and now also to some of these things called ‘media agencies’. This time I got a very different response.

2 OFFERS + 1 VERY PERSUASIVE MAN = ONE BIG DECISION

I went to see TMD; I went to see Abbott Mead Vickers (who had rejected me the first time because I didn’t have an Oxbridge degree). Then, on one day in November, I had two interviews; in the morning with The Media Business and in the afternoon with an ad agency called SJIP/BBDO.

First I met Allan Rich at The Media Business. I still remember his silk shirt and gold medallion, his arm draped across the back of the sofa.

At the end of the conversation he said: “I’d like you to join, your first day will be 2 January, your starting salary will be £3,750. Have a nice Christmas.” He didn’t even ask me if I wanted the job!

That afternoon I saw Sean McCormick, the media director of SJIP/BBDO, and I walked through the door and this was Mad Men. Beautiful receptionists, people smoking, drinking, sitting with their feet up, drawing pictures in cool offices. This was exactly what I’d pictured in my head. At the end of the interview he offered me a job starting in January at £4,250.

I said, “I have to be honest,” and I told him about the offer from The Media Business. He said to just go home, think about it, we’ll bike you a contract. I went home and within an hour, sure enough, a bike arrived with the contract. This was what I wanted. An ad agency offering me a contract. I still didn’t really get what these “media independents” did. They didn’t get mentioned in the careers room at school.

So I rang Allan Rich the next morning, and said, this is terribly embarrassing, but I did have one more interview after I saw you yesterday, and they offered me a job, and it seems to me – from what I understand – that you’re in a very specialised area of advertising, and I’m not sure I’m ready to specialise. I think I need to find out about the whole industry, and maybe specialise later. I think I need to take the other job.

And he said to me – and this was probably the worst conversation I ever had with Allan – “You are making the biggest fucking mistake of your life. I’m telling you: this is where the future is. The future is not with agencies like SJIP/BBDO. In fact, we have a shared client, and I’d go as far as to say that they will be out of business within two years. Young Stevie, I’m going to give you 45 minutes to change your mind, or don’t ever bother to speak to me again for the rest of your life.” And he slammed the phone down.

I put the phone down, and I was literally shaking. I rang Mike Yershon and asked his advice, and he basically said he couldn’t help me, this was a decision I needed to make on my own.

To this day I don’t know exactly why I chose The Media Business, but I think Allan was just the most incredibly persuasive person I’d met. So I rang him and said, “I’m going to stick with you, and if it’s still okay, I’ll turn up on 2 January.” I suppose I just believed in what he was saying – the passion in his voice.

Allan was always the first into the office in the mornings; I was usually the second. One morning, almost exactly two years later, I was upstairs in the kitchen making my first cup of coffee of the day, and Allan walked in, holding the new edition of Campaign. He slapped the front cover: “There you go, I told you!” And there was the headline, ‘SJIP/BBDO goes out of business.’

SELLING THE IDEA OF SPECIALISATION

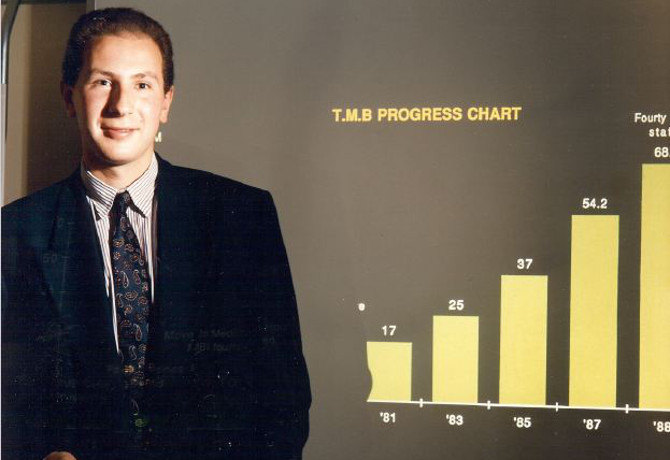

I joined The Media Business in 1982. In 1988, I was made new business director. I was the first dedicated new business director in a media agency, and it was uphill work. I still remember the stress of cold-calling clients: “Who? What? What do you do? No thanks.”

In those days the norm was for the ad agency to handle the media planning and buying. Up until the day Zenith came into existence we spent at least 50% of our time selling the sector – selling the idea of specialisation – and only then talking about why clients should use TMB rather than TMD.

Today, of course, that’s completely taken for granted.

The original direct clients of media agencies were those who didn’t really need the skills of an ad agency: typically record companies, because the product was totally the hero, the direct-sell buccaneers – K-Tel and Ronco – and also several Japanese clients, who seemed to be less tied to the traditional way of doing business. One of our first clients was Panasonic. The first I won as new business director was Citizen Watches.

90% of our clients were shared clients with creative agencies, often new launches that didn’t have media departments. BBH had started, there was an agency called Astral, and we basically acted as their media departments.

In fact we often had to go through this charade of pretending we were their media department, if that was how the ad agency wanted to play things.

I remember, several years down the track, pitching with an ad agency, and they wanted me to give a card out saying I was media director of the ad agency, but one of the clients in the room knew me, and knew I worked at TMB. So that was embarrassing.

As time went on, I realised I didn’t like the way media was treated as the afterthought, the way we were always the back-room boys. Fortunately, that was changing.

Another significant impact of the birth of media agencies. I think it’s often overlooked – and I doubt if it was in Paul Green’s original vision – that it gave the space for new ad agencies to be launched. I don’t think BBH or Howell Henry Chaldecott Lury would have launched, or certainly they would have struggled, without media agencies. The fact that their clients could use media agencies for their media made those new generations of creative agencies much easier to launch.

And equally, they were great for us. The new wave of agencies like HHCL were quite happy for us to do the media – none of that pretending to be their media department nonsense – and they brought to us a kind of client that, up till then, we weren’t getting close to: exciting, challenger brands who were looking for innovative solutions.

We were starting to win bigger clients, but it wasn’t until first Ray Morgan and Partners split away from Benton and Bowles, and then, in 1988, when they became subsumed into Zenith that things really changed.

ZENITH: THE GAME-CHANGER

When Saatchi set up Zenith we knew it was big news because Saatchi was the biggest agency in the world, but it would be post-rationalising to suggest that we immediately knew what it meant. Having said that, the speed with which more and more clients started making media-only appointments after that was very rapid. So it wasn’t long before we realised, “This is our moment.”

Other agencies followed suit, setting up their own versions of Zenith. Grey set up the first incarnation of MediaCom. Pretty soon most of the major agencies had their own ‘media dependent’, as they were called.

So major clients were now separating their media, and that legitimised the whole sector. We no longer had to sell the concept before we sold the benefits of TMB.

THE NEED FOR SCALE

In October 1993, at the tender age of 30, I had been made group managing director of TMB and so began to take a wider view of the emerging trends in the industry.

Smaller ad agencies were panicking, because they could see that volume and scale were the order of the day. So good agencies like CDP and GGT were wondering what to do. They had clients like RHM, Boots, Cadburys – all talking about centralisation, putting all the media for all their brands into one company – and they feared that they would lose the media budgets that they currently controlled to bigger companies. They decided that their best option was to combine their media, and further bulk it up by acquiring TMB.

Conversations weren’t easy. The media director of GGT, Julian Neuberger [currently CEO of MediaCom South Africa], grew increasingly intransigent as we tried to reach agreement over roles and responsibilities.

The trade press got hold of the story, and ran the story as if it was a done deal. Funnily enough, that just accelerated the termination of the conversations.

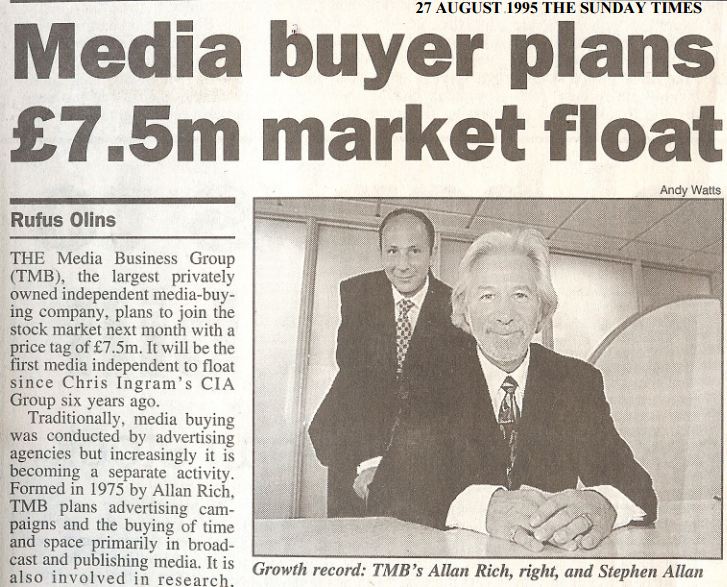

We looked instead at other ways to grow. We decided the best course of action was to seek a public listing on the London Stock Exchange, because this would give us access to funds that would allow us to exponentially grow the size of the business. One of the areas we were looking at was regional expansion.

So I found myself at the age of 32 – alongside Allan – running a public company, which provided a whole new set of experiences. Rather than pitching to advertisers for their business, we were now pitching to institutions for their money.

Life became quite ‘grown-up’: we had a board of non-execs, I had to learn about Remuneration Committees and Nomination Committees and so on.

We launched as a ‘penny stock’ and sometimes, in the past, ‘penny stocks’ had not had the best reputation, so this made it difficult to approach some institutions. This was a marketing challenge – not unlike our earlier efforts to be taken seriously by some advertisers. Later we did a one-for-ten share consolidation, thus removing the penny stock stigma.

THE NEED FOR GLOBAL SCALE

That strategy worked well for a while, but it pretty soon became clear that as The Media Business we were going to reach a brick wall. We were never going to be able to pitch for – never mind win – Coca Cola or GSK, or whoever, without a network. Having got the benefits of centralising their media within one country, major advertisers were now looking to centralise all their media in a region or globally.

The media agency that made the deepest inroads into building a network was CIA, the forerunner of MEC. We had what was termed a “wired network”, where we were wired into Initiative. We won global business like Converse Shoes and Motorola on the back of that. It was a reasonable solution, but it wasn’t really for the long-term.

We knew we needed a more long-term global solution; meanwhile, there were global agencies out there who needed more scale in the UK.

MEDIACOM 2.0

Interpublic were interested in acquiring us as part of their drive to set up a second network, Western. We were also approached by Grey.

There was one trip to New York where Allan Rich and I met with Phil Geier in the morning and Ed Meyer in the afternoon.

I remember being led into a room to wait for Ed Meyer, and offered a drink by a butler. Allan always had a thing about air conditioning – it was never cold enough for him – and while the butler was away fetching the drinks, he got out of his chair and started fiddling with the air conditioning controls. The butler returned, and in a tone of shocked disapproval said, “You mustn’t touch Mr Meyer’s air conditioning.”

Despite that, things went well. Ed only had two questions: “Allan, tell me about you and tell me about your family’s background.” Then he asked me the same.

Having won VW in Germany, they wanted to win the VW business in the UK – which they believed would trigger winning it around the world – and they didn’t fancy their chances as they were. That was their motivation for a deal.

We got nine months into negotiations. Word got out and we had to make an announcement to the takeover panel.

We’d floated at 30p. Prior to the announcement we were trading at 60p, and as soon as there was an announcement they went up to 120p.

Ed came to see us in London, and said he was reducing the price, and we said no. And negotiations ended.

Several weeks later, with the VW opportunity still hanging over them, Grey came back to us. Alexander Schmidt-Vogel – a rising star within MediaCom/Grey who was at that time running EMEA – called me on a Thursday afternoon, and he said, “I realise that you must be very angry with us, and you may not want to talk to us, but I still want to do this deal. I’m at the Langham Hotel, please come over and talk.”

So we met up that night and we had what we consequently referred to as “the Schnitzel dinner”.

It was obvious to both of us that the deal made sense to both parties. We couldn’t stand another long drawn-out deal and a long period of uncertainty, so I said, “Okay, we can propose a deal to management and shareholders, if it’s all lined up within three days.”

So we did the deal over that weekend.

When we joined forces, we became the sixth biggest agency. Zenith was largest and still double our size. And that’s when I stood up in front of the combined staff and said, “In three years’ time we’ll be number one.”

And we were.

REACHING NUMBER ONE IN THE UK

Before us, most mergers in the media industry had been quite difficult affairs, with a lot of client and staff fall-out. In comparison, ours was one of the most successful mergers in our industry. That’s not to say we didn’t have teething troubles: the big learning curve for me was just how territorial people can be. I remember there was a fight – literally a fight – over a filing cabinet.

Claire Beale wrote a leader in Campaign which was very critical, saying we had no personality, and describing the merged company as “a wisp of fog waiting to take shape”. I photocopied it 250 times and had it put on everyone’s pinboard. Right, I thought, we’ll show them.

To be fair to Claire, when she wrote that in 1999, she wasn’t suggesting that we were a terrible agency, just that she couldn’t see what was different about us. Understandably, we were immensely proud when – 10 years later – Campaign named us as Media Agency of the Decade; and it was particularly pleasing that the write-up began “It’s an agency like no other…”!

The first piece of shared business that we won together was IPC magazines; then VW, which was hugely important, and also very difficult.

We were shown off by the network to VW as the shiny new toy – look we’ve done this to our London office for you. But that backfired, because the UK marketing team had no intention at all of letting their German HQ tell them what to do.

So it was supposed to be an advantage for us, but in fact it was a problem. The UK team came up with every possible excuse they could think of not to work with us, and it turned out to be, probably, the longest pitch ever – 13 months.

After that we went on a winning run: the COI, some P&G print buying, Mars planning, then Wrigley (Mars and Wrigley were different companies then). We added to the GSK business, Iceland, RBS and Sky.

We did the Sky pitch against Mindshare. It was very important to Ed that we won – he wanted to show Martin Sorrell that “his boys” were better!

It soon became clear why. I met with Ed in Cannes that summer to tell him about an acquisition opportunity; but when I met with him he was just not there at all, not engaged, not really listening – it wasn’t like him at all. I remember finding Nick Lawson, and saying, “I’m sure Ed’s about to sell the company”. Twenty-four hours later Grey made an announcement that they had appointed Goldman Sachs to look into “strategic opportunities”. And, soon afterwards, WPP bought Grey.

MEDIACOM UK’S FORMULA FOR WINNING BUSINESS

The merger gave us a degree of critical mass, and it ticked the international box.

We then defined for ourselves a good market position – ‘Closer to Clients’. That was helpful in a market where there’s actually surprisingly little clear positioning.

We had great people, which we did and still do – no question.

And we developed a winning formula in pitches. For a while we were the only agency really doing pitch theatre.

Theatre had to enhance the message, not just be theatre for theatre’s sake. It wasn’t about gimmicks, it was about coming up with a simple, powerful visual idea that enhanced the message of the pitch. Like doing the Mars pitch in a sweet shop. It was different, and it also underlined the message that we understood the challenges they faced at retail; that this wasn’t about “coverage and frequency”, it was about selling more product.

Our idea was quite simply that if a client team had seen four or five very similar-sounding media agency pitches, with similar names and similar ideas, presented in similar language, using similar techniques, they wouldn’t be arguing about the fine detail of each media strategy, they would spend most of the time actually struggling to remember which agency said what. But we reckoned they would definitely remember the guys who did the pitch on roller skates.

THE NEXT PHASE OF CONSOLIDATION

In 2006, Sir Martin Sorrell asked me if I would set up and run GroupM in the UK. GroupM already existed as an informal concept, but now it was time to set it up properly – a company to oversee WPP’s media agencies: at that time MediaCom, Mindshare, MEC and BJK&E (which later became Maxus).

I remember asking colleagues in the US, “What’s the playbook? What’s the wiring diagram?” – and there wasn’t one. So we had to invent our own model. We became a “recessive enabler” – it was vital in my view that the agencies remained the heroes.

We gave them better resource and capability; trading was key – the combined scale of GroupM opened doors. We accelerated the digital capabilities, and also did some ground-breaking things, like setting up GroupM Entertainment. I always like to set big goals, and I said GroupM Entertainment could become the UK’s biggest independent production company – and its well on track for that.

When we set up GroupM, MEC had come through a pretty torrid time; and I think during the first three years of GroupM, we really helped CEO Tom George and his management team to turn it around, and make it a top-five agency in the UK.

Meanwhile, MediaCom and Mindshare continued to prosper as the number one and number two agency, so, by the time I left GroupM, we had three of the top five.

PROTECTING OUR POSITION

By the early 2000s the shape of the industry as we see it today was pretty much formed.

Our task back then was to protect the position that we at MediaCom had won.

The growth of the Internet – and proliferation of digital technologies – forced the media agencies to look over their shoulders and think, “Now we need to raise our game to compete with the new generation of digital agencies that are setting up.”

If the media agencies hadn’t responded – and we weren’t as quick to respond as we could have been – media agencies as such could have become irrelevant then.

The moment we become complacent about our position, is the moment we will start to lose it to some new challengers

That’s an important lesson. It’s possible to look at the last quarter century and see simply the triumphant rise and rise of the media agency. But we must always remember: first, that it could easily have turned out differently; and second, that everything will continue to change, and that the moment we become complacent about our position, is the moment we will start to lose it to some new challengers.

I think it’s this refusal to become complacent – and the understanding that we need to continually re-think and refresh our offering – that has helped MediaCom in the UK stay at number one for well over a decade now, and has helped move the network up from sixth to third position during some of the toughest economic conditions most of us can remember.

PEOPLE FIRST

Choosing the right team is so often the difference between success and failure; and the idea that you should surround yourself with clever people – maybe a bit cleverer than you are – isn’t just a cliché, it’s absolutely true.

All the way through, I’ve had a team of brilliant people around me. And this has made everything easier. It meant, for example, that when I took the GroupM job, I knew that I could leave MediaCom in the safe hands of Nick Lawson.

When I took the global CEO role at MediaCom in 2008, I knew that I could bring Nick Lawson across to run EMEA, knowing that Jane Ratcliffe was there to take over the helm in the UK, backed up by a team of amazing people, like Karen Blackett, Sue Unerman and Claudine Collins.

There is this core team – simply too many to mention here – that somewhat unusually for this industry – have come up through the ranks together, and stayed together for 15, 20 or even more years.

MediaCom’s belief is “People first … better results”, and it’s not just a nice phrase that we stick up on a poster on the wall in a corridor somewhere; it’s something we really do believe in, and that we try to make real. Something that began with Allan and lives on today.

With the rapid change in our industry, we need to constantly re-evaluate just about everything: our offering to clients, our tools and products, the kind of people we want to hire, the very nature of the company. But a belief is something that you should always stay true to – something that should never change.

Ironically, the more our industry becomes obsessed with data and technology, the more important “People first” becomes, because the people you have in the company – and what those people do with all that data and technology – remains your only real point of differentiation.